Spotting greenwashing is not about finding lies, but about recognising the strategic distractions brands use to hide their unsustainable core business models.

- Verifiable data from third-party audits (like B Corp) is the only reliable proof, not a brand’s own ‘Conscious’ label.

- The true cost of a cheap garment is paid by underpaid workers and in environmental waste, regardless of its ‘natural’ or ‘recycled’ material claims.

Recommendation: Shift your focus from marketing claims to the brand’s fundamental business model: Is it built on high volume and disposability, or on longevity and accountability?

The scene is familiar to any British shopper: a prominent display in a high street store, adorned with soft green signage, proclaiming a new “Conscious” or “Sustainable” collection. The fabrics feel soft, the marketing speaks of a better world, and the prices are still temptingly low. It feels like a guilt-free way to stay on-trend. But in the back of your mind, a question lingers: is this a genuine commitment to change, or just a sophisticated marketing strategy to make you buy more?

The common advice is to look for certifications, read the labels, or choose natural fabrics. While well-intentioned, this approach is no longer sufficient. Brands have become masters of greenwashing, using vague language and focusing on minor positive attributes to distract from a fundamentally unsustainable business model. This is where the perspective of a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) auditor becomes essential. An auditor doesn’t take claims at face value; they demand evidence, scrutinise data, and assess what is truly material to a company’s impact.

The real key to seeing through the greenwash is not just spotting buzzwords, but conducting your own mini-audit. It’s about learning to differentiate between a brand’s stated intent and its measurable impact. This requires shifting your focus from the product’s label to the brand’s entire operational structure, from the transparency of its supply chain to the integrity of its environmental claims. It is about demanding a verifiable chain of custody, not just a comforting story.

This guide will equip you with that auditor’s framework. We will move beyond the surface-level checks and provide a rigorous methodology to deconstruct sustainability claims, verify evidence, and ultimately distinguish authentic ethical practice from opportunistic marketing fiction. You will learn to assess a brand’s claims with the same critical eye as a professional, empowering you to make truly informed decisions.

For those who prefer a visual summary, the following video offers a powerful overview of the greenwashing phenomenon in the fashion industry, perfectly complementing the detailed audit techniques we will explore.

To navigate this complex landscape, we have structured this guide to methodically break down the key areas of scrutiny. The following sections will walk you through the critical checkpoints of an effective consumer audit, from deciphering certifications to understanding the true lifecycle of your clothes.

Contents: A Forensic Guide to Ethical Fashion Claims

- Why the B Corp label is more reliable than a brand’s self-declaration

- How to trace the origin of a £15 t-shirt’s cotton?

- Fast Fashion “verte” vs Slow Fashion : qui paie le prix réel ?

- L’erreur de confondre “naturel” et “écologique” sur les étiquettes

- Par où commencer : remplacer les basiques par des marques éthiques britanniques

- Production de masse suisse ou atelier boutique anglais : quel modèle soutenir ?

- The mistake of believing “100% recycled” means infinitely recyclable

- Swiss Ancestral Expertise vs. British Watchmaking Revival: Who Wins?

Why the B Corp label is more reliable than a brand’s self-declaration

In a sea of self-proclaimed “eco-friendly” lines, the first principle of any audit is to seek independent, third-party verification. A brand’s internal “Conscious” label is a marketing asset; a certification like B Corp is a legally binding commitment that has been rigorously vetted. B Corp is not a product certification; it is a comprehensive assessment of a company’s entire social and environmental performance, from its supply chain and materials to its employee benefits and community engagement.

The process is intentionally demanding. To become a Certified B Corporation, a company must complete the B Impact Assessment, achieving a minimum verified score of 80 on a scale that measures its impact on five pillars: Governance, Workers, Environment, Community, and Customers. This isn’t a one-time badge; companies must recertify every three years, demonstrating continuous improvement. This data is made public, creating a level of transparency that a simple brand-owned logo can never match. With recent data showing that more than 1,000 B Corp certified companies operate in the UK, with London leading globally, there is a growing ecosystem of verifiable businesses.

Case Study: Baukjen’s B Corp Journey vs High Street Competitors

The UK fashion brand Baukjen provides a clear example of this difference. Achieving its B Corp certification in March 2021, the company scored in the top 5% of all B Corps for its governance practices. Their public Impact Assessment details legally binding commitments across all five areas. This stands in stark contrast to the vague, unaudited claims of many high street “conscious” collections, which lack the crucial element of external accountability and legally enforceable standards.

When you see a B Corp logo, you are seeing the result of a thorough audit. It signifies that the company has legally amended its corporate governance structure to be accountable to all stakeholders—not just shareholders. This is the fundamental difference between a marketing claim and a verified business model.

How to trace the origin of a £15 t-shirt’s cotton?

The deceptively simple “Made in…” label on a garment is one of the most common red herrings in fashion. It typically refers only to the final stage of assembly—where the pieces were stitched together. For a cotton t-shirt, this completely obscures the long and complex journey of the raw material: the cotton farm, the ginning facility, the spinning mill, the weaving or knitting plant, and the dyeing house. True transparency requires a complete chain of custody, something a £15 price point makes almost impossible to achieve ethically.

Tracing the origin of cotton is critical because its production is fraught with environmental and social risks, from intensive water usage and pesticide pollution in conventional farming to forced labour in regions like Xinjiang. A brand that cannot or will not disclose the specific origin of its raw materials is not a transparent brand. The complexity of this global network is often used as an excuse for opacity, but truly responsible brands invest in the systems needed to map and monitor their suppliers.

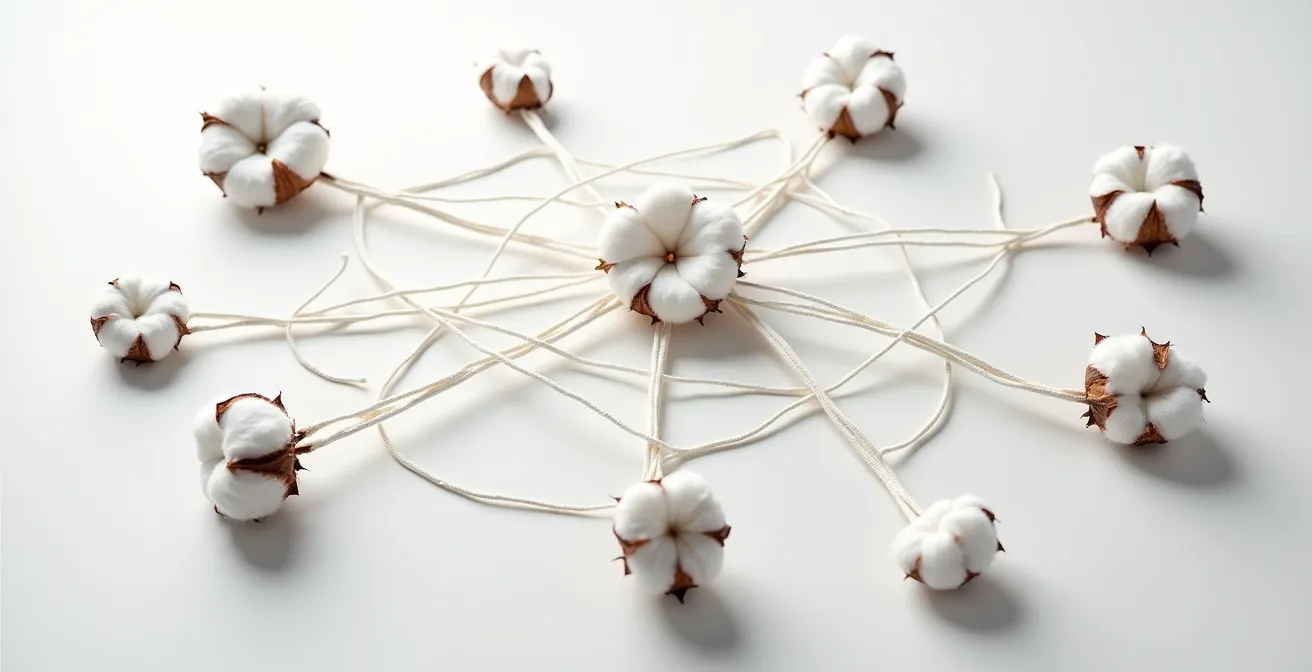

As the visualisation suggests, the modern textile supply chain is a sprawling web of global actors. Without a clear map, claims of “sustainably sourced” are meaningless. An auditor’s job is to demand that map. As a consumer, your role is to question any brand that cannot provide it. The absence of information is, in itself, a significant piece of data.

Your Action Plan: Verifying Cotton Origin

- Check for GOTS Certification: The Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) is a world-leading standard that mandates strict chain of custody verification for organic fibres, from farm to final product.

- Look Beyond the “Made in” Label: Remember this only shows the final assembly location. Ask about the source of the fabric and the raw cotton itself.

- Use Verification Tools: Apps like Good On You perform deep research into brand transparency and provide ratings on their supply chain traceability.

- Search for QR Codes: While still rare, some forward-thinking brands are adding QR codes to labels that link directly to supply chain information.

- Engage Directly: Ask retailers or contact the brand’s customer service to request their supply chain documentation. A legitimate, transparent brand will have this information and should be willing to share it.

“Green” Fast Fashion vs. Slow Fashion: who really pays the price?

The concept of “green” fast fashion is, for many auditors, a fundamental contradiction. The fast fashion business model is built on high-volume production, rapid trend cycles, and low prices, all of which encourage overconsumption and disposability. A brand might introduce a t-shirt made from organic cotton, but if it produces millions of them and the core business model relies on customers treating clothing as a single-use item, the net impact remains profoundly negative. This is a classic case of focusing on one small “good” to distract from the material damage of the overall system.

The low price tag of fast fashion hides immense externalised costs. This “true cost” is not paid by the brand or the consumer, but by garment workers and the environment. The 2020 scandal in Leicester, where an investigation revealed that workers were paid as little as £3.50 an hour to produce clothes for major high street names, is a stark reminder of the human price. This was happening right here in the UK, demonstrating that geographic proximity is no guarantee of ethical labour.

In contrast, slow fashion is a philosophy built on the opposite principles: quality over quantity, timeless design over fleeting trends, and fair pricing that reflects the true cost of production. A higher upfront cost for a slow fashion item often translates to a lower cost-per-wear over time, in addition to reduced social and environmental harm. The following comparison breaks down the real-world implications.

| Factor | Fast Fashion (£15 top) | Slow Fashion (£50 dress) |

|---|---|---|

| Cost per wear (10 wears vs 50 wears) | £1.50 | £1.00 |

| Textile waste contribution | Part of 300,000 tonnes/year UK waste | Reduced through longevity |

| Worker conditions | Often below minimum wage | Living wage more common |

| Environmental cost | High (frequent disposal) | Lower (extended use) |

This data reveals that the “affordability” of fast fashion is an illusion. The real price is paid in the form of environmental degradation and human exploitation, factors that are systematically excluded from the ticket price. An auditor’s duty is to bring these hidden costs to light.

The mistake of confusing “natural” and “eco-friendly” on labels

One of the most effective greenwashing tactics is the conflation of “natural” with “sustainable.” Marketers leverage our intuitive preference for natural materials, implying that anything grown from the earth is inherently good for it. An auditor, however, knows to look at the data behind the material’s full lifecycle. Conventional cotton is a prime example: while it is a natural fibre, its production is one of the most environmentally damaging in agriculture.

The statistics are staggering. According to industry analysis, conventional cotton requires 2,700 litres of water to produce one shirt, equivalent to what one person drinks in 2.5 years. It is also responsible for a significant portion of the world’s insecticide and pesticide use, which pollutes waterways and harms biodiversity. So, a t-shirt labelled “100% Natural Cotton” might sound wholesome, but its environmental footprint can be enormous. This is a critical distinction that marketing deliberately blurs.

In contrast, other natural fibres with a strong heritage in the UK, such as linen (from flax) and hemp, are genuinely more eco-friendly. These crops are resilient, require significantly less water and few to no pesticides to grow, and can thrive in European climates. Yet, they often receive less marketing attention than “natural” cotton or exotic but questionable materials like bamboo viscose, which involves a highly chemical-intensive process to turn the hard plant into soft fabric.

The lesson here is to be skeptical of the “natural” halo effect. The origin, cultivation method, and processing of a fibre are far more important than its classification as natural or synthetic. True sustainability lies in the measurable data of its impact, not in its pastoral marketing appeal.

Where to start: replacing basics with ethical British brands

After deconstructing the complex claims and misleading narratives, the question becomes practical: what is the first step? The temptation is to purge your wardrobe and immediately start buying from “better” brands. However, the most sustainable action is often the one that involves no purchasing at all. It begins with a shift in mindset away from acquisition and towards longevity.

This sentiment is perfectly captured by a leading voice in the sustainable fashion movement. As an auditor would advise, the first point of data to consider is what you already possess.

The most ethical basic is the one you already own

– Gemma Metheringham, Circular fashion researcher

This powerful statement reframes the problem. The goal is not to become a better consumer, but to consume less. Repairing a garment, finding a good tailor, and simply wearing your clothes more are the most impactful first steps. However, when a replacement for a staple item becomes truly necessary, a strategic approach is required. Instead of a complete overhaul, focus on replacing your high-rotation basics—the t-shirts, jeans, and knitwear that form the foundation of your wardrobe.

This is where supporting local, ethical British brands can be a tangible action. Many smaller UK-based companies are built on principles of transparency, using high-quality materials and paying fair wages to local artisans. By choosing to invest in a well-made basic from a transparent British brand, you are not only acquiring a durable garment but also supporting a business model that directly opposes the fast fashion system. It is a targeted investment in the kind of fashion industry you want to see exist.

Mass-market Swiss production or English boutique workshop: which model to support?

The debate over production models often gets framed as a choice between anonymous, industrial-scale efficiency and artisanal, localised craftsmanship. We can think of this as “mass-market” versus “boutique workshop.” The former, often associated with the precision and scale of industries like Swiss watchmaking, prioritises volume and cost reduction. The latter, exemplified by a revival of small-scale English workshops, prioritises transparency, community value, and skill.

From an auditor’s perspective, the “better” model is not determined by its country of origin or its romantic appeal, but by its accountability and social impact. The mass-market model’s complexity and scale often create opacity, making it difficult to trace materials or verify labour conditions. The boutique model, by its very nature, tends to be more transparent. When production happens locally and at a smaller scale, it is easier to ensure workers are paid fairly and that processes are managed responsibly.

Case Study: Community Clothing’s UK Manufacturing Revival

East London’s Community Clothing, a B Corp certified brand, perfectly illustrates the value of the boutique workshop model. Operating on a made-to-order basis, they create limited-edition pieces with skilled local workers. Their knitwear is made by older women at Age UK community centres, while dresses are crafted at Stitches in Time in Limehouse, providing skilled employment to refugee communities. This model doesn’t just produce clothes; it creates profound social value, demonstrating how fashion can be a force for strengthening local communities within the UK.

This is not to say that all large-scale production is inherently bad, or all small-scale production is good. However, when you support a brand like Community Clothing, you are voting for a system where the creators are visible, valued, and integrated into their community. You are supporting a model where social profit is as important as financial profit. For a consumer-auditor, this verifiable local impact provides a level of assurance that a faceless global supply chain rarely can.

Key Takeaways

- A brand’s business model—high-volume and disposable vs. low-volume and durable—is more revealing than its marketing.

- Third-party certifications like B Corp are the gold standard for verification, as they involve rigorous, independent audits.

- “Natural” and “recycled” do not automatically mean sustainable; you must investigate the full lifecycle and impact of the materials.

The mistake of believing “100% recycled” means infinitely recyclable

The claim “made from 100% recycled materials” is one of the most prevalent and misleading in the greenwashing playbook. It creates the comforting illusion of a perfect, closed-loop system where old clothes are magically reborn as new ones. The reality is far more complex and less impressive. An auditor must scrutinise what “recycled” actually means in practice, as the term hides a process that is often one of downcycling, not true recycling.

Most “recycled polyester” (rPET) used in high street fashion is not made from old polyester clothing. It is made from downcycled PET plastic bottles. While this diverts plastic from landfill, it is not a circular solution for fashion. The resulting fabric is of lower quality than virgin polyester and cannot be easily mechanically recycled again. Furthermore, with some reports showing that less than 15% of textiles worldwide were recycled in 2024—and only 1% truly recycled back into new clothing—the scale of the problem is immense. The vast majority of collected clothing is either exported, incinerated, sent to landfill, or downcycled into lower-value products like insulation or rags.

This disconnect between marketing and reality means that a t-shirt made from “recycled materials” is often just a temporary stop for plastic waste on its way to the landfill, all while shedding microplastics with every wash. The claim creates a feel-good factor that encourages more consumption, without solving the fundamental waste problem. True circularity, where old garments are chemically broken down and reformed into new fibres of the same quality, is still technologically immature, energy-intensive, and not available at scale.

Believing the simple “100% recycled” tag without asking deeper questions is a critical error. It allows brands to benefit from an environmental halo while perpetuating a linear, disposable system. The claim serves the brand’s marketing far more than it serves the planet.

Swiss Ancestral Expertise vs. British Watchmaking Revival: Who Wins?

Ultimately, the battle against greenwashing comes down to a clash of philosophies. On one side, we have “Swiss Ancestral Expertise”—a metaphor for the established brands that rely on a reputation built over decades, using marketing nostalgia and heritage claims as a proxy for quality and trust. On the other, we have the “British Watchmaking Revival”—representing a new generation of brands, often based in the UK, whose claim to expertise is not based on history, but on radical transparency, sustainable innovation, and verifiable ethics.

From an auditor’s standpoint, historical reputation is irrelevant; current, verifiable data is everything. A brand that has existed for 100 years but cannot trace its supply chain is less trustworthy than a five-year-old brand that publishes its full factory list and has B Corp certification. The “winner” in this contest is not the one with the better story, but the one with the better evidence. Expertise in the 21st century is defined by a brand’s ability to innovate towards a more just and sustainable model.

Case Study: Make it British and the New Definition of Expertise

Yorkshire-based manufacturer Banana Moon exemplifies this new model. They achieved B Corp certification with a high score of 85.3, proving that UK manufacturers can compete on ethics and quality. They implemented Direct to Garment printing technology that reduced their water consumption by 25%. This revival of innovative UK manufacturing shows that modern ‘expertise’ is about measurable improvements in sustainability, not just romantic heritage claims. It proves that all business models, whether built on ‘Swiss precision’ or ‘British heritage’, must evolve beyond marketing nostalgia to earn consumer trust.

The final verdict is clear: the winning model is the one that embraces accountability. It is the one that substitutes vague stories for hard data, marketing for materiality assessments, and heritage for holistic responsibility. As a consumer-auditor, your role is to reward this new definition of expertise. The power lies in choosing the brand that is willing to prove its worth today, not the one that simply asks you to trust its past.

Your next purchase is an opportunity to conduct an audit. Apply this rigorous framework to question claims, demand transparency, and invest your money only in those brands that can unequivocally prove their positive impact.

Frequently Asked Questions about Greenwashing in Fashion

Is recycled polyester (rPET) truly sustainable?

No – it’s typically downcycled from plastic bottles, not old clothes, cannot be easily recycled again into high-quality fabric, and it sheds harmful microplastics with every single wash.

What happens to clothes in UK take-back schemes?

The outcomes are mixed and often disappointing. A large percentage of collected clothes are exported to other countries, some are downcycled into rags or insulation, and only a tiny fraction—often less than 1%—is truly recycled fibre-to-fibre into new clothing.

Why can’t synthetic fabrics be infinitely recycled?

The most common form of recycling, mechanical recycling, physically shreds the material, shortening the fibres and degrading their quality with each cycle. Chemical recycling, which can create virgin-quality fibres, is a promising alternative but remains extremely energy-intensive, expensive, and is not yet widely available at a commercial scale.